This is a partial draft (July 28, 2005 of part 9 of The Emotion Machine by Marvin Minsky. Do not distribute this because it will change. All comments welcome: send them to minsky@media.mit.edu.

Chapter §9. The Self............................................................................ 1

We need Multiple Models of Ourselves........................................... 4

Multiple Sub-Personalities............................................................... 5

The Sense of Personal Identity......................................................... 6

§9-2. Personality Traits....................................................................... 7

Self-Control...................................................................................... 8

Dumbbell Ideas and Dispositions..................................................... 9

§9-3. Why do we like the idea of a Self?........................................... 12

§9-4. What is Pleasure, and why do we like it?................................. 14

The Pleasure of Exploration........................................................... 16

§9-5. What controls the mind as a whole?.......................................... 17

Mental Bugs and Parasites............................................................. 21

Why don’t we have more bugs than we do?................................... 21

§9-6. Why makes feelings so hard to describe?................................. 22

§9-7. How do you know when you’re feeling a pain?...................... 24

Feelings are hard to describe because they are complex!................ 25

§9-8. The Dignity Of Complexity..................................................... 27

§9-9. Some Sources of Human Resourcefulness.............................. 27

Chapter §9. The Self.

Could be

I only sang because the lonely road was long;

and now the road and I are gone

but not the song.

I only spoke the verse to pay for borrowed time:

and now the clock and I are broken

but not the rhyme.

Possibly,

the self not being fundamental,

eternity

breathes only on the incidental.

—Ernesto Galarza, 1905-1984

What makes each human being unique? No other species of animal has such diverse individuals; each person presents a different set of appearances and abilities. Some of those traits are inherited, and some come that person’s experiences—but in every case, each of us ends up with different characteristics. We sometimes use ‘Self’ for the features and traits that distinguish each person from everyone else.

However, we also use Self in a sense which implies that all our activities are controlled by powerful creatures inside ourselves, who do our thinking and feeling for us. We call these our Selves or Identities, and sometimes we tend to think of them as like separate persons inside our heads.

Daniel Dennett: “A homunculus (from Latin, 'little man') is a miniature adult held to inhabit the brain … who perceives all the inputs to the sense organs and initiates all the commands to the muscles. Any theory that posits such an internal agent risks an infinite regress … since we can ask whether there is a little man in the little man's head, responsible for his perception and action, and so on.”[1]

What attracts us to the queer idea that we can only think or feel with the help of those Selves inside our minds? Chapter §1 suggested some reasons for this:

Citizen: Whether or not you believe that Selves exist, I’m perfectly sure that there’s one inside me, because I can feel it working to make my decisions.”

Psychotherapist: The Single-Self legend helps makes life seem pleasant, by hiding from us how much we’re controlled by goals that we’d rather not know about.

Pragmatist: The Single-Self concept helps make us efficient by keeping our minds from trying to understand everything all the time.

The Single-Self view thus keeps us from asking difficult questions about our minds. If you wonder how your vision works, it answers that: ‘Your Self simply peers out though your eyes.” If you ask how your memory works, you get: “Your Self knows how to recollect whatever might be relevant.” And if you wonder what guides you through your life, it tells that your Self provides you with your desires and goals—and then solves all your problems for you. Thus, the Single-Self view diverts you from asking about how your mental processes work, and leads you to wonder, instead, about these kinds of questions about your Self:

Is an infant born with anything like what an adult would call a Self’? Some would insist on answering with, “Yes, infants are persons just like us—except that they don’t yet know so much." But others would take an opposite view: “An infant begins with almost no intellect, and developing one takes a sizeable time.”

Does your Self have a special location in space? Most ‘western’ thinkers might answer, “Yes”—and tend to locate it inside their heads, somewhere not far behind their eyes. However, I’ve heard that some other cultures situate Selves between the belly and chest.

Which of your beliefs are your “genuine” ones? The Single-Self view suggests that some of your many intents and views are your “sincere” and ‘authentic” ones—whereas the models of mind discussed in this book leave room for a person to hold conflicting values and attitudes.

Does your Self stay the same throughout your life? We each have a sense of remaining the same, no matter whatever may happen to us. Does this mean that some part of us is more permanent than our bodies and our memories?

Does your Self survive the death of your brain? Different answers to that might leave us pleased or distressed, but would not help us to understand ourselves.

Each such question uses words like self, we, and us in a somewhat different sense—and this chapter will argue that this is good because, if we want to understand ourselves, we’ll need to use several different such views of ourselves.

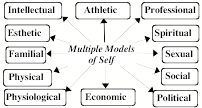

Whenever you think about your “Self,” you are switching among a network of models[2], each of which may help to answer questions about different aspects of what you are.

For example, some of our models are based on simplistic ideas like “All our actions are based on the will to survive,” or “we always like pleasure more than pain,” while some other self-models are far more complex. We develop these multiple theories because each of them helps to represent certain aspects of ourselves, but is likely to give some wrong answers about other questions about ourselves.

Citizen: Why should a person want more than one model? Would it not be better to combine them into a single, more comprehensive one?

In the past, there were many attempts to make ‘unified’ theories of psychology.[3] However, this chapter will suggest some reasons why none of those theories worked well by itself, and why we may need to keep switching among various different views of ourselves.

Jerry Fodor: “If there is a community of computers living in my head, there had also better be somebody who is in charge; and, by God, it had better be Me.”[4]

Cosma Rohilla Shalizi: “I have been reading my old poems, and they were written by somebody else. Yet I am that selfsame person; or, if I am not, who is? If no one is, when did he die—when he finished this poem, or that one, or the next day, or the end of that month?”—

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-1. How do we Represent Ourselves?

“O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!”—Robert Burns 1759-1796

How do people construct their self-models? We’ll start by asking simpler questions about how we describe our acquaintances. Thus, when Charles tries to think about his friend Joan, he might begin by describing some of her characteristics. These could include his ideas about:

The appearance of Joan’s body and face,

The range and extents of her abilities,

Her motives, goals, aversions, and tastes,

The ways in which she is disposed to behave,

Her various roles in the social world,

However, when Charles thinks about Joan in different realms, his descriptions of her may not all agree. For example, his view of Joan as a person at work is that she is helpful and competent, but tends to undervalue herself; however, in social settings he sees her as selfish and overrating herself. What could lead Charles to make such different models? Perhaps his first representation of Joan served well to predict her social performance, but that model did not well describe her business self. Then, when he changed that description to also apply to that realm, it made new mistakes in the contexts where it formerly worked. Eventually, he found that he had to make separate models of Joan to predict her behaviors in other roles.

Physicist: Perhaps Charles should have tried harder to construct one single, more unified model of Joan.

This would not be feasible, because each of a person’s mental realms may need different kinds of representations. Indeed, whenever a subject becomes important to us, we build new kinds of models for it—and this ever-increasing diversity must be a principal source of our human resourcefulness.

To more clearly see the need for this, we’ll turn to a simpler situation: Suppose that you find that your car won’t start. Then, to diagnosis what might be wrong, you may need to switch among several different views of what might be inside your car:

If the key is stuck, or the brake won’t release, you must think in terms of mechanical parts.

If the starter won’t turn, or if there is no spark, you must think in terms of electrical circuits.

If you’ve run out of gas, or the air intake’s blocked, you need a model of fuel and combustion.

It is the same in every domain; to answer different types of questions, we often need different kinds of representations. For example, if you wish to study Psychology, your teachers will make you take courses in at least a dozen subjects, such as Neuropsychology, Neuroanatomy, Personality, Perception, Physiology, Pharmacology, Social Psychology, Cognitive Psychology, Mental Health, Child Development, Learning Theories, Language and Speech, etc. Each of those subjects uses different models to describe different aspects of the human mind.

Similarly, to learn Physics, you would need subjects with names like these: Classical Mechanics; Thermodynamics; Vector, Matrix and Tensor Calculus; Electromagnetic Waves and Fields; Quantum Mechanics; Physical Optics; Solid State Physics; Fluid Mechanics; Theory of Groups, and Relativity. Each of those subjects has its own ways to describe the events that occur in the physical world.

Student: I thought that physicists seek to find a single model or “grand unified theory” to explain all phenomena in terms of some very small number of general laws.

Those ‘unified theories of physics’ are grand indeed—but to apply them to any particular case, we usually need to use some specialized representation to deal with each particular aspect of what all the scientists of the past have discovered. Thus, whenever we deal with complex subjects like Physics or Psychology—we find ourselves forced to split such fields into ‘specialties’ that use different representations to answer different kinds of questions. Indeed, a major part of education is involved with learning when and how to switch among different representations.

Returning to Charles’ ideas about Joan, these will also include some models of Joan’s own views about herself. For example, Charles might suspect that Joan is displeased with her own appearance (because she is constantly trying to change this) and he also makes models of how Joan might think about herself in realms like these.

Joan’s ideas about her own ideals.

Her ideas about her abilities,

Her beliefs about her own ambitions,

Her views about how she behaves,

How she envisions her social roles.

Joan would probably disagree with some of Charles views about her, but this may not make him change his opinion because he knows that the models that people make of their friends are frequently better than the models that people make of themselves. As programmer Kevin Solvay has said, [5]

"Others often better express myself.”

We need Multiple Models of Ourselves

“... But even as these ordinary thoughts and perceptions flowed unimpeded, a new kind of question seemed to spin through the black space behind them all. Who is thinking this? Who is seeing these stars, and citizens? Who is wondering about these thoughts, and these sights? And the reply came back, not just in words, but in the answering hum of the one symbol among the thousands that reached out to claim all the rest: Not to mirror every thought, but to bind them. To hold them together, like skin. Who is thinking this? I am.” —Greg Egan[6]

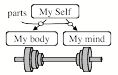

We’ve discussed a few models that Charles might use when he thinks about his friend Joan. But what kinds of models might people use when they try to think about themselves? Perhaps our most common self-model begins by representing a person as having two parts—namely, a 'body' and a 'mind'.

That body division soon then grows into a structure that describes more of one’s physical features and parts. Similarly, that model of mind will divide into a host of parts that try to depict one’s various mental abilities.

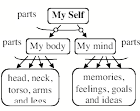

However, any model one makes of oneself will only serve well in certain situation, so we each end with different views of ourselves to use in different realms, in which each person has different goals and capabilities. This means when we think about ourselves, we’ll needs ways to radiply switch among different models we’ve made of ourselves.

Any single model that tried to represent all this would soon become too complex to use. For, in each of those various realms of life, the models that we make for ourselves will portray us as having had somewhat different autobiographies, in which we pursued somewhat different aims, and ideals, while maintaining various different beliefs and making different interpretations of the same events. This suggests another idea about what one might mean when one tries to talk about one’s self:

Daniel Dennett: "... we are all virtuoso novelists, who find ourselves engaged in all sorts of behaviour, and we always try to put the best "faces" on if we can. We try to make all of our material cohere into a single good story. And that story is our autobiography. The chief fictional character at the centre of that autobiography is one's self." [7]

Multiple Sub-Personalities.

"For there is not a single human being ... who is so conveniently simple that his being can be explained as the sum of two or three principal elements... Harry consists of a hundred or a thousand selves [but] it appears to be an inborn and imperative need of all men to regard the self as a unit. … Even the best of us shares the delusion. " —Herman Hesse, in Steppenwolf.

When Joan is with a group of her friends, she regards herself as fairly sociable. But when surrounded by strangers she sees herself as anxious, reclusive, and insecure. For, we each make different self-models to use in different kinds of contexts and realms, just as we said in chapter §4: to think of herself.

Joan’s mind abounds with varied self-models—Joans past, Joans present and future Joans; some represent remnants of previous Joans, while others describe what she hopes to become; there are sexual Joans and social Joans, athletic and mathematical Joans, musical and political Joans, and various kinds of professional Joans.

Thus each person has a variety of ‘sub-personalities,’ ach of which may have some control over different sets of resources and goals, to be used when playing different—so that each has somewhat different ways to think. However, all of one’s sub-personae will generally share most of one’s skills and bodies of commonsense knowledge. However, conflicts among those sub-personalities can lead to problems because some of them might make rash decisions, while others might try to take over and maintain control.

For example, suppose that Joan is working at her professional job—but suddenly some social part of her mind reminds her of a time when she was trapped in an awkward relationship. She tries to shake off those memories, only to find herself thinking in childish ways about how her parents would view her present behavior. Thus Joan’s thoughts might oscillate among such varying self-images as:

A partner in a business,

A person who likes to do research,

One with a certain collection of values,

A member of a family,

A person involved in a love affair,

A person having a pain in her knee.

In the course of such trains of everyday thinking, we frequently switch between different self-models, whose various outlooks may not be consistent, because we use them for different purposes. This means that when Joan needs to make a decision, the result will partly depend upon which sub-personalities are active then. A Business Self might be inclined to choose the option that seems more profitable; an Ethical Self might want to select the that suits her ideals ‘best’; a Social Self might want to select the one that would most please her friends. For example, when we identify ourselves as members of a social group, then we can share their triumphs and failures with exuberance or remorse, and thus exhibit concern, compassion, and empathy. Thus, as we said in Chapter §1, each major change in emotional state may display a different sub-personality:

When a person you know has fallen in love, it's almost as though someone new has emerged—a person who thinks in other ways, with altered goals and purposes. It's almost as though a switch had been thrown, and a different program has started to run.

Whenever we switch among sub-personalities, we are likely to change our ways to think—but because the context remains the same, we will still maintain some of the same of priorities, goals, and inhibitions, some contents of short-term memories, and some of our currently active Mental Critics.

However, some such changes may be larger, and we often hear sensational stories about persons who switch between totally different personalities. However, while such extremes are exceedingly rare, everyone undergoes changes of mood in which one exhibits somewhat different sets of intentions, behaviors and traits. Some of these shifts will be transiently brief, while others will be more persistent—but in each case, the sub-personality that is now in control will influence the views and goals that you use and pursue, and may claim that these are the views and goals of what it believes to be the ‘genuine’ You.

The Sense of Personal Identity

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo: “Of what nature am I? A life various, manifold, and vast. Behold in the numberless halls and caves, in the countless fields and dens and caverns of my memory, full without measure of numberless kinds of things— present there either through images as all bodies are; or present in the things themselves as are our thoughts; or by some notion or observation as our emotions are, which the memory retains though the mind feels them no longer...” —Confessions.

In everyday contexts it often makes sense to think of one's Self as a permanent thing. But to what extent are you the same as you were ten minutes ago? Or are you like a carving knife that has had both its handle and blade replaced?

You’re certainly not like the text of a book whose pages remain eternally unchanged; your ‘contents’ keep changing moment to moment. Nevertheless over months and years, enough of your knowledge remains the same—and different enough from anyone else’s—that we recognize your stability. For one can argue that our ‘identities’ are mainly what’s in our memories.

“A man is often willing to say that this is the same person who did something in the past, not on the basis of knowing that it is the same body but on a quite different basis—that the person recounts the past situation with great accuracy, exhibits similar personal reactions, and displays the same skills.”—Encyclopedia Britannica:

A mind is an assembly of parts that each performs different activities. Each may have conflicting concerns and goals, which sometimes can only be resolved by turning off some participants. But then, when you change the way you think, what would it mean to say that you’re still the same? Of course, that depends on how you describe yourself. To some of your models of yourself, significant parts of you will have changed—whereas, to some of your other models, you may remain unchanged. Consequently, it won’t often make sense to ask what your Identity is. Instead, it usually would be better to ask, which of your models of yourself would best serve your present purposes.

“Our brains appear to make us seek to represent dependencies. Whatever happens, where or when, we're prone to wonder who or what's responsible. This leads us to discover explanations that we might not otherwise imagine, and that helps us predict and control not only what happens in the world, but also what happens in our minds. But what if those same tendencies should lead us to imagine things and causes that do not exist? Then, perhaps that strange word ‘I’—as used in ‘I just had a good idea’—reflects the selfsame tendency. If you're compelled to find some cause that causes everything you do-why, then, that something needs a name. You call it ‘me.’ I call it ‘you.’"—SoM §22-7

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-2. Personality Traits.

"Whatever you say something is, it is not." —Alfred Korzybski[8]

If you asked Joan to describe herself, she might say something like this:

Joan: “I think of myself as disciplined, honest, and idealistic. But because I am awkward at being sociable, I try to compensate by trying to be attentive and friendly, and when that fails, by being attractive.”

Similarly, if you were to ask Charles to describe his friend Joan, he might declare that she is helpful, tidy, and competent, but somewhat lacking in self-confidence. Such descriptions are filled with everyday words that name what we call “character traits” or “characteristics”—such as disciplined, honest, attentive, and friendly. But what could make it possible for someone to describe a person at all? Why should minds so complex as ours show any clear-cut characteristics? Why, for example, should anyone tend to be usually neat or usually sloppy—rather than tidy about some things but not about others? Why should personal traits exist at all? Here are some possible causes for the appearance of such uniformities:

Inborn Characteristics. Two person could be born with the same resources, e.g., for becoming angry or afraid—but may differ in the conditions or priorities in which those functions become aroused—so that one of those individuals may tend to be more belligerent than the other one.

Investment Principle: Once we learn an effective way to do some job, we’ll resist learning other ways to do it—even when we are told about some other technique that is better for this—because that new method will be more awkward to use until we become proficient at it. So, as our old procedures gain strength, it gets harder for new ones to compete with them.

Archetypes and Self-Ideals: Every culture comes with myths that describe the fates of beings that are endowed with larger-than-life traits. Few of us can prevent ourselves from becoming attached to those heroes and villains. Then some of us may adopt some goals of trying to guide how we change ourselves, to make those imagined traits become real.

Self-Control: It is hard to achieve any difficult goals unless you can make yourself persist at them. But one can’t simply ‘tell yourself’ to persist, because different circumstance are likely to make one change ones goals and priorities. So again, one may end up by training oneself.

Stereotyping: Whenever we encounter something, we assume ‘by default’ that it must be like other things that it reminds us of. This can yield such good results that we come to ignore other differences.

Of course, one could argue that personal traits don’t really exist, but that trait-based descriptions are popular because, although they may wrong or incomplete, they seem so simple and understandable. For, perhaps the easiest way to describe a thing is by making a simple list of its properties. Thus we can describe a child’s building block as being rectangular, heavy, and made of wood. Similarly, it is easy to say that a person is honest and tidy—as opposed to being deceitful and sloppy. However, of course, no person always tells the truth, or keeps everything perfectly neat. Nevertheless, it can save a great deal of effort and time to see people or things as stereotypes—by assuming their properties by default.

However, even when we know those assumptions may be wrong, they still may continue to influence us, so the concept of traits can be treacherous. Here is a common example of this: suppose that some stranger you’ve never met were to take your hand, look into your eyes, and then report this impression of you:

“Some of your aspirations tend to be unrealistic. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary and reserved. You have found it unwise to be too candid in revealing yourself to others. You are an independent thinker and do not accept others' opinions without good evidence. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety, and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

“At times you have serious doubts as to whether you made the right decision or did the right thing. Disciplined and controlled on the outside, you tend to be anxious and insecure inside. Your sexual adjustment has presented some problems for you. You have a great deal of unused capacity, which you have not turned to your advantage. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself, but have a strong need for other people to like and to admire you.” [9]

Many people are amazed that a stranger could see so deeply inside of them—yet every one of those statements applies, to some extent, to everyone! Just look at the adjectives in that horoscope: affable, anxious, controlled, disciplined, extroverted, frank, independent, insecure, introverted, proud, reserved, self-critical, self-revealing, sociable, unrealistic, wary. Everyone has concerns in regard to each of those characteristics, so few of us can help but feel that each such prediction applies to us.

Thus, millions of people have been entranced by the prophecies of so-called psychics, fortune-tellers, and astrologers—even when those forecasts are confirmed no more often than chance would predict. [10] Why do we give so much credence to them? One reason could be that we trust those “seers” more than we trust ourselves, because they appear to be ‘reliable authorities.’ Another possible cause could be that we tend to believe that we are already like what we wish to be—and fortune-tellers excel at guessing what most people most want to hear. But perhaps the simplest reason why such assessments may seem correct to us is that we each maintain so many self-models that almost any statement about ourselves will agree with at least some of those models.

Self-Control.

It is hard to achieve any difficult goals unless, at least to some extent, you can make yourself persist at them. You would never complete any long-range plans if, whatever you tried, you kept “changing your mind.” However, you cannot simply ‘decide’ to persist, because many kinds of events may later affect your goals and priorities. Consequently, we each must develop ways to impose less breakable self-constraints on ourselves.

For example, if you should ever need help from your friends, they will need to know what to expect from you—and to know when they can depend on you—and therefore, at least to some extent, you must make yourself predictable. Furthermore, it is important for you to be able to ‘depend on yourself’ to carry out at least some of your many plans, so again you need ways to restrict yourself. Our cultures help to us to acquire such skills by teaching us to admire various traits of consistency, commitment, and ambitiousness. Then if you come to admire those traits, you may make it your goal to train yourself to behave in those ways.

Citizen: Might not such restrictions cause you to pay the price of losing your spontaneity and creativity?

Artist: Creativity does not result from lack of constraints, but comes from discovering appropriate ones. Our best new ideas are the ones that lie just beyond the borders of realms that we wish to extend. An expression like “skdugbewlrkj” may be totally new, but would have no value unless it connects with other things that you already know. [11]

In any case, it is always hard to make yourself do things that do not interest you—because, unless you have enough self-control, the Rest of Your Mind will find more attractive alternatives. §4-7 showed how we sometimes control ourselves by offering bribes or threats to ourselves in the forms of self-incentives like, “If I fail, I’ll be ashamed of myself,” or " I’ll be proud if I can accomplish this.” To do this requires some knowledge about which such methods will work on ourselves—but generally, it seems to me, the techniques we use for self-control resemble those that we use to persuade our acquaintances— e.g., exploiting their various needs and fears by making promises of rewards or withdrawing their access to things that they want. Here are several other such tricks:[12]

Admonish yourself, "Don't give in to

that."

Try exercise, or take deep breaths.

Ingest caffeine or other brain-affecting chemicals.

Set your jaw, or furrow your brow. [Facial

expressions work especially well because they affect you as much as they do

your audience.]

But why must you use such devious tricks to select and control your ways to think—instead of just choosing to do what you want to do? The answer is that you soon would be dead if any particular part of your mind could take over control of all the rest— and our species would quickly become extinct if we were able to simply ignore the demands of hunger or pain or sex. But fortunately, we evolved systems whereby, whenever we faced emergencies, our most urgent instinctive goals can supersede our fantasies.

Along with those built-in priorities, every human culture develops ways to help its members constrain themselves. For example, every game that our children play helps to train them to assume new roles and to swiftly switch among those mental states, while still obeying the rules of that game—which, in effect, is a virtual world. Therefore, and perhaps most important of all, every child should also recognize that a game is only a game. Alas, that’s one lesson too few of us learn.

Self-Control is no simple skill, and many of us spend much of our lives seeking ways to make our minds ‘behave.’ Eventually, we each accumulate techniques whose workings are so opaque to us that we can only use vague suitcase-words for them; this leads to yet one more meaning for ‘Self’—our name for all the methods we use whenever we try to control ourselves.

Dumbbell Ideas and Dispositions.

There

are two rules for success in life.

First, never tell anyone all that you know.

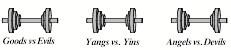

Why do we find it so easy to say that a certain person tends to be extroverted and sociable—as opposed to being shy and reclusive? More generally, why do we find it so easy to make such two-part distinctions for other aspects of our personalities? Thus we often group our tempers, emotions, moods and traits into pairs that we regard as opposites.

Solitary

vs. Sociable Dominant vs. Submissive

Tranquil vs. Agitated Careless vs. Meticulous

Forthright vs. Devious Cheerful vs. Cranky.

Audacious vs. Cowardly Joyous vs. Sorrowful

But what inclines us to describe our traits in terms of these kinds of two-part pairs when, for example, Agitation clearly is not the mere absence of Tranquility, nor is Joy just the absence of Sorrow? One explanation could be that this reflects a more general human tendency to see many other aspects of our minds as split into pairs of seemingly opposite qualities.

Left vs. Right

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

Thought vs. Feeling Deliberate vs. Spontaneous

Rational vs. Intuitive Literal vs. Metaphorical

Logical vs. Analogical Reductionist vs. Holistic

Intellectual vs. Emotional Scientific vs. Artistic

Conscious vs. Unconscious

Serial vs. Parallel

We see similar ‘dumb-bell’ thinking at work when people try to describe the rest of the world in terms of opposing pairs of forces, spirits, or principles.

Perhaps the most amusing instance of this is the popular myth that each person has two distinct kinds of mental activities that are embodied in opposite sides of the brain. In earlier times, the two halves of the brain seemed so alike that they were thought to be almost identical. But then, in the mid-20th century, when surgeons could cut the connections between those halves (in an adult), they were found to have some significant differences.[13] Then both press and public embraced the idea that every brain had two distinct and opposing sides—and this revived many views of the mind as a place for conflicts between such pairs of antagonists:

But how could so many such different distinctions be embodied in the same two halves of the very same brain? The answer is that this is largely a myth; a brain contains hundreds of different resources, and each of those activities involves many of these on both sides of the brain. However, there still may be some truth to that myth, but one can construct better explanations for this. For example, it long has been known that the ‘dominant’ side develops more machinery for language-based activities—and this could lead to more extensive development of self-reflective levels of thinking, while leaving more on the opposite side for spatial and visual activities. Here is what I think might be involved in this:

In early life, we start with mostly similar agencies on either side. Later, as we grow more complex, a combination of genetic and circumstantial effects leads one of each pair to take control of both. Otherwise, we might become paralyzed by conflicts, because many agents would have to serve two masters. Eventually, the adult managers for many skills would tend to develop on the side of the brain most concerned with language because those agencies connect to an unusually large number of other agencies. The less dominant side of the brain will continue to develop, but with more emphasis on lower-level skills, and with less involvement with plans and goals. Then if that brain-half were left to itself, it will seem more childish and less mature because it lacks those higher-level management skills. [14]

Here are some other reasons why we might like making two-part distinctions so much:

Many things seem to have Opposites. It could be that, in early life, it is hard to distinguish what something ‘is’ without some idea of what it is not—and so we tend to think about things in relation to their possible opposites. For example, it often makes sense to classify physical objects as large or small, or as heavy or light, or as cold or hot.

However, when you ask a young child about such things, you re likely to hear that the opposite of water is milk, that the opposite of dog is cat, or that the opposite of a spoon is a fork. But that very same child may also insist that the opposite of fork is knife. Thus opposites depend on the contexts they’re in, and so may overrule consistency.

Intensities and Magnitudes. Although it is hard to describe what feelings are, it seems easy to say how intense they are. This makes it seem quite natural to apply such adjectives as slightly, largely, or extremely’ to almost every emotion word—such as sorry, pleasant, happy, or sad.

One often justifies a choice, simply by declaring that one likes this option more than that one. However, sorrow is not the mere absence of joy—nor is pleasure merely the absence of pain, nor is appetizing an opposite to disgusting. It can be convenient to mis-represent such pairs as like the two ends of a single line, but doing this too frequently could lead to one-dimensional ways to think, no matter that such two-part distinctions may blur other dissimilarities between pairs of substantially different ideas, by leading us into supposing that both sides of each pair are almost the same—except for having ‘plus’ or ‘minus’ signs! Thus, representing feelings in terms of intensities can simplify how we make our decisions. However, I suspect that when we face more difficult choices, then we use more complex ways to settle conflicts among competing views or ways to think. [15]

Structural vs. Functional descriptions. Many of our distinctions are based on ways to make connections between what we learn about things and what we learn about using those things. Accordingly, it is often convenient to classify the parts of an object as playing ‘principal’ vs. ‘supporting’ roles—just as we did for ‘a chair’ in §8-3, where we identify the seat and back as its essential parts, and its legs and parts as merely serving to sustain them. [16]

Certainly, two-part distinctions can be useful when we need to choose between alternatives—but when that fails, we may have to resort to more complex distinctions. For example, when Carol is trying to build that Arch, it will sometimes suffice for her to first describe each block as being short or tall, or narrow or wide, or thin or thick; then she may only need to decide which of those distinctions is relevant. However, on other occasions, Carol may need to find a block that satisfies some more elaborate combination of constraints that relate its height, width and depth; then she can no longer describe that block in terms of only a single dimension.

![]()

Inborn Brain-Machinery. Another reason why we tend to think in terms of pairs could be that our brains are innately equipped with special ways to detect differences between pairs of mental representations.

In §6-4 we mentioned that when you touch something very hot or cold, the sensation is intense at first, but then will rapidly fade away—because our external senses mainly react to how things change in time. (This also applies to our visual sensors, but we're normally unaware of this because our eyes are almost always in motion.) If this also applies to sensors inside a brain, this would make it easy to compare a pair of descriptions, simply by alternately presenting them. However, this ‘temporal blinking’ scheme would work less well for describing the relationships of more than two things—and that could be one reason why we are less proficient at making three-way comparisons. [See SoM §23.3 Temporal Blinking]

When is it appropriate to distinguish between only two alternatives? We often speak as though it is enough to classify a new thing or event in ‘yes or no’ terms like these:

Was this a failure or a success?

Should we see it as usual or exceptional?

Should we forget it or remember it?

Is it a cause for pleasure or for distress?

Such two-part distinctions can be useful when we have only two options to choose among. However, selecting what to remember or do will usually depend on making more complex decisions like these:

How should we describe this event?

What links should we connect it with?

Which other things is it similar to?

What other uses could we make of it?

Which of our friends should we tell about it?

More generally, it usually little sense to commit ourselves, for all future times, about which objects to like or dislike—or about which persons, places, goals, or beliefs we should seek or avoid, or accept or reject—because all such decisions should depend, upon the contexts that that we find ourselves in.

Accordingly, it seems to me that there is something wrong with most dumbbell distinctions: those divisions appear to be so simple and clear that they seem to be all that you need—and that satisfaction tempts you to stop. Yet most of the novel ideas in this book came from finding that two parts are rarely enough—and eventually my rule became: when thinking about psychology, one never should start with less than three hypotheses!

Why do people find it so hard to classify things into more than two kinds? Could this be because our languages don’t come with verbs for speaking about trividing things? We all are good at ‘comparing’ pairs of things, and making lists of their differences—but few of us ever develop good ways to talk or to think about trifferences—that is, about relationships among triplets of things. Could this be because our brains don’t come equipped with adequate, built-in techniques for this?

Perhaps this could be in part because a typical child’s environment contains almost no significant ‘triplets’ of things. A typical two-year-old has a pair of hands, and is taught by a pair of parents to learn some way to put on a pair of shoes—and, soon, that typical two-year-old will learn to understand and to use word “two.” perhaps from being familiar with such pairs as two hands or two shoes. But it usually takes yet another full year for that child to learn to use the word “three.”

Robert Benchley: “There are two kinds of people in the world: those who believe there are two kinds of people in the world and those who don't.”

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-3. Why do we like the idea of a Self?

Brian: You are all individuals!

Mob: We are all individuals!

Lone voice: I'm not. [17] — Monty

Python: The Life of Brian

Most of the time we think of ourselves as having definite identities.

Introspectionist: I do not feel like a scattered cloud of separate parts and processes. Instead, I sense that there’s some sort of Presence in me—an Identity, Spirit, or Feeling of Being—that governs and guides all the rest of me.

Other times we find ourselves feeling less decisive or less centralized.

Citizen: One part of me wants this, while another part of me wants that. I need to get more control of myself.

A few unusual persons claim never to feel any such sense of unity. Thus one philosopher went so far as to say,

Josiah Royce: "I can never find out what my will is by merely brooding over my natural desires, or by following my momentary caprices. For by nature I am a sort of meeting place of countless streams of ancestral tendency. … I am a collection of impulses. There is no one desire that is always present to me."[18]

In any case, even when we feel that we’re in control, we recognize conflicts among our goals. Then we may argue inside our minds, and try to find a compromise—but sometimes we still find ourselves subject to compulsions and urges we can’t overcome. And even when we feel unified, others may see us as disorganized.

We solve easy problems in routine ways, scarcely thinking about how we accomplish these—but when our usual methods don’t work, then we start to ‘reflect’ on what went wrong with what we were attempting to do—and this chapter maintains that we do such reflections by switching around in a great network of ‘models’— where each purports to represent some facet or aspect of ourselves. Thus what we call ‘Self’ in everyday life is a loosely connected collection of images, models, and anecdotes.

In fact, if this view of the Self is correct, then there is nothing so special about it—because that’s how we represent everything else, namely, as a Panalogy. Thus when you think about a telephone, you keep switching among different views of its appearance, its physical structure, the feelings you have when you use it, etc. It’s the same when you think about your Self; you still may be using the same kinds of techniques that you use to think about everyday things; different parts of your mind are engaged with a variety of models and processes. But if so, then what impels us to believe that that we must be anything more than Josiah Royce’s meetings of streams? What leads us to the strange idea that our thoughts cannot just proceed by themselves?

Jerry Fodor: “If there is a community of computers living in my head, there had also better be somebody who is in charge; and, by God, it had better be Me.”[19]

Citizen: Even if no central Self exists, you’d have to explain why we feel that one’s there. When I think my thoughts and imagine things, must not there be someone who’s doing those things!

After all, if we had those Single Selves to want and feel and think for us, then we would not have much need for Minds—and if our Minds could do those things by themselves, then it would be of no use to have those Selves? Then how could that curious ‘Self” idea ever help us to understand anything? Aha! Perhaps that is precisely the point: we use words like ‘Me’ and ‘I’ to keep us from thinking about what we are! For they all give the very same answer, “Myself,” to every such question that we might ask. Here are some other ways in which that Single-Self concept is useful to us:

A Localized Body. You cannot walk through solid walls, or stay aloft without support. Where any part of your body goes, the rest of you must also go—and the Single-Self model includes the idea of being in only one place at a time.

A Private Mind. It is pleasant to think of your Self as like a strong, closed box, so that no one else can share your thoughts to learn the secrets you want to keep—for only you hold the keys to those locks.

Explaining our Minds. Perhaps it seems to make sense to say things like, ‘I perceive the things that I see,’ because we know so very little about how our perceptions actually work. This way, that Single-Self view can help to keep us from wasting time on questions we don’t know answers to.

Moral Responsibility. Each culture needs behavioral codes. For example, because our resources are limited, we sometimes have to censure Greed. Because we each depend on others, we have to chastise Treachery. And to justify our laws and decrees, we have to assume that some Single Self is ‘responsible’ for every willful, intentional deed.

Centralized Economy. We’d never accomplish anything if we kept asking questions like, “Have I considered every alternative?” We prevent this with Critics that interrupt us with, “That’s enough thinking; I’ve made my decision!”

Causal Attribution. When we represent any thing or event, we like to attribute some Cause to it. So when we don’t know what led to some thought, we assume that the Self was the cause of it. This way, we sometimes may use the word ‘Self’ the way we say ‘it’ in “it started to rain,” because we don’t know a more plausible cause.

Attention and Focus. We often think of our mental events as occurring in a single ‘stream of consciousness’—as though they all were emerging from some single, central kind of source, which can only attend to one thing at a time. We’ll discuss this more in §§Attention.

Social Relations. Other people expect us to think of them as Single Selves, so unless we adopt a similar view, it will be hard to communicate with them.

These all are good reasons why the Single-Self view is convenient to use in our everyday lives. But when we want to understand how we think, no model so simple as that can portray enough useful details of how our minds work. For even if ‘you’ had some way to observe your entire mind simultaneously, that would be too complex to comprehend—so you still would be compelled to switch among simplified models of yourself.

Why should those models be simplifications? That’s because we would be overwhelmed by seeing too many unwanted details. That’s what makes a map more useful to us than seeing the entire landscape that it depicts; a good model helps us to focus on only those features of things that might be significant in some particular context. A good map or model may also include additional knowledge, as when the blueprint of a house shows the dimensions its parts were intended to have, as well as the name of its architect.)

The same applies to what we store in our minds. Consider how messy our minds would become if we filled them up with descriptions of things whose details had too little significance. So instead, we spend large parts of our lives at trying to tidy up our minds—selecting the portions we want to keep, suppressing others we’d like to forget, and refining the ones we’re dissatisfied with. [20]

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-4. What is Pleasure, and why do we like it?

We may lay it down that Pleasure is a movement by which the soul as a whole is consciously brought into its normal state of being; and that Pain is the opposite. If this is what pleasure is, it is clear that the pleasant is what tends to produce this condition, while that which tends to destroy it, or to cause the soul to be brought into the opposite state, is painful. —Aristotle, Rhetoric, I, 10.

We tend to feel pleased—or at least relieved—when we accomplish something we want. Thus, as we remarked in chapter 2,

“When Carol recognized that her goal was achieved, she felt satisfaction, fulfillment and pleasure—and those feelings then helped her to learn and remember.”

Of course, we’re delighted that Carol felt pleased—but how did those feelings help her to learn—and why do we like those feelings so much, and work so hard to find ways to attain them? Indeed, what does it mean to say that someone feels “pleased?” When people answer questions like these, we frequently hear examples of circular reasoning:

Citizen: I do the things that I like to do because I get pleasure from doing them. And naturally, I find them pleasant because those are the things that I like to do.”

Certainly, we all can agree that pleasure is a feeling we ‘get’ when we’re in a condition that we like—but that does not help much to explain what words like pleasure and liking mean. Our Dictionaries reflect the same problem:

Pleasure: a feeling of delight, happiness, or satisfaction.

Satisfaction: the pleasure that comes when a need is fulfilled.

Liking: a feeling of enjoying something or finding it pleasant [21]

One reason why we get into such circles is that we don’t have good ways to describe any feelings. To be sure, we find it rather easy to say how weak or strong a feeling feels—but when we are asked for more details, we usually cannot describe the feeling itself, but can only resort to analogies like, “That pain was as piercing as a knife.”

However, this should lead us next to ask what could make something so hard to describe. It seems to me that this is likely to happen when we fail to find a way to divide that thing—be it an object or mental a condition—into several separate parts (or layers, or phases, or processes). This is because a thing that we cannot split into parts gives us nothing to use as pieces of explanation! In particular, it is a popular view that pleasure is “elemental” in the sense that it cannot be explained in terms of anything else, and that the quest for pleasure or satisfaction is a “basic” human drive. Here is a parody of that idea:

Product Promoter: Happiness is the ultimate goal of all human beings, and all of us constantly aim toward this, whether through leisure, career, wealth, relationships or whatever. Our secure online ordering system offers a line of carefully chosen products to help you replace discomfort with pleasure.

However, this section will argue that what we call pleasure is indeed a suitcase-name for quite a few different processes that involve activities that we don’t often recognize. For example, we usually see Pleasure as positive, but one can see it as negative—because of how it tends to suppress other competing activities. Indeed, to accomplish any major goal, one must suppress others that might compete with it, as in, “I don’t feel like doing anything else.” Discussing this is important because, it seems to me, the assumption that pleasure is simple or ‘elemental’ has been an obstacle to understanding our psychology. To see what is wrong with that idea, we’ll catalog some of the feelings and activities that make this subject so difficult.

Satisfaction. A species of pleasure called ‘satisfaction’ comes when an ambition has been achieved.

Exploration. We may also feel pleasure during a quest—and not only at the end of it. So it is not only a matter of being rewarded for achieving a goal.

Relief. A species of pleasure called “relief “may come when a problem has been solved—if that goal was represented as an irritation or agitation.

Joy and Bliss. Sometimes, when you enter a pleasant state you feel, if only transiently, as though all of your problems had been solved!

Critic-Suppression. “I know this could be bad for me, but I like it so much that I’ll do it anyway.”

Credit Assignment and Learning. Perhaps the most important aspects of pleasure are its connections with learning and memory.

Success can also fill you with pleasure and pride—and may also motivate you to show other persons what you have done. But the pleasure of success soon fades (at least for ambitious intellects) because, shortly after we put one problem to rest, another one quickly replaces it. For few of our problems stand by themselves, but are only parts of larger ones.

Also, after you’ve solved a difficult problem, you may feel relieved and satisfied, and sometimes may also feel a need to arrange for some sort of inner or outer celebration. Why might we have such rituals? Perhaps there’s a special kind of relief that comes when one can dismiss a goal and release of resources that it engaged—along with the stresses that came with them. Clearing out one's mental house may help to make other things easier—just as the ‘closure’ of a funeral can help to assuage a person’s grief.

But what if the problem you’re facing persists? You can sometimes regard your present distress as a benefit, as in "I’m certainly learning a lot from this,” or “Others may learn from my mistakes." And everyone knows this magical trick for turning all failures into success: one can always tell oneself “The true reward is the journey itself.”

So instead of trying to say what Pleasure is, we’ll need to develop more ideas about what processes might be involved in what we often describe in simple terms such as “feeling good.” In particular, it seems to me that we often use words like pleasure and satisfaction refer to an extensive network of processes that we do not yet understand—and when anything seems so complex that we can’t grasp it all at once, then we tend to treat it as though it were single and indivisible.

Pleasures are ever in our hands or eyes,

And when in act they cease, in prospect, rise:

Present to grasp, and future still to find,

The whole employ of body and of mind. —Alexander Pope, in Essay on Man

The Pleasure of Exploration.

“Pleasure pursues objects that are beautiful, melodious, fragrant, savory, soft. But curiosity, seeking new experiences, will even seek out the contrary of these, not to experience the discomfort that may come with them, but from a passion for experimenting and knowledge.” —St. Augustine, in Confessions, 35.55.

Understanding a new and difficult subject—or exploring an unfamiliar terrain—can lead to a lot of pain and stress. Then how can we keep this from holding us back from learning new ways to accomplish things? One antidote for this is Adventurousness.

“Why do children enjoy the rides in amusement parks, knowing that they will be scared, even sick? Why do explorers endure discomfort and pain—knowing that their very purpose will disperse once they arrive? And what makes people work for years at jobs they hate, so that someday they will be able to—they seem to have forgotten what! It is the same for solving difficult problems, or climbing freezing mountain peaks, or playing pipe organs with one's feet: some parts of the mind find these horrible, while other parts enjoy forcing those first parts to work for them.” —The Society of Mind, §9.4.

Most of our everyday learning involves only minor adjustments to skills that we already know how to use. One can do this by using ‘trial and error; one makes a small change, and if that results in a pleasant reward (such as being pleased with an improved performance) then that change will become more permanent.[22] This fact has led many teachers to recommend that ‘learning environments’ should mainly consist of situations in which pupils get frequent rewards for success. To promote this, then, one should help the students to progress through a sequence of small, easy steps.

However, this strategy won’t work well in unfamiliar realms because, when we learn a substantially new technique, this will involve more work with less frequent rewards, while enduring the additional stress of being confused and disoriented. It also may require us to abandon older techniques and representations that previously have served us well—and this might even arouse a sense of loss that brings “negative” feelings akin to grief. Such periods of awkwardness and ineptitude would usually cause a person to quit.

This suggests that that "pleasant" or “positive” practice, alone, may not suffice for us to learn more radically different ways to think. This, in turn suggests that to become proficient at learning new things, a person must somehow acquire what Augustine called, in the extract above, ‘a passion for experimenting and knowledge.’ Such persons must somehow have managed to train themselves to actually enjoy those discomforts.

Citizen: How can you speak of ‘enjoying’ discomfort? Isn’t that a self-contradiction?

It is only a contradiction when you regard your Self as a single Thing. But when you see the mind as a society, then you no longer have to think of pleasure as an all-or-none thing. For now you can imagine that, while some parts of your mind are uncomfortable, other parts of your mind may enjoy forcing those first parts to work for them. For example, one part of your mind can still represent your state in a positive way by saying "Good, this is a chance to experience awkwardness and to discover new kinds of mistakes!''

Citizen: But wouldn’t you still be feeling that pain?

Indeed, when struggling at their seemingly punishing tasks, athletes still feel physical pain, and artists and scientists feel mental pains—but, somehow, they seem to have trained themselves to keep those pains from spiraling into the awful cascades we call ‘suffering.’ But how could those persons have learned to suppress, ignore, or enjoy those pains, while preventing those disruption cascades? To answer that, we would need to know more about our mental machinery.

Scientist: Perhaps this does not really need any special explanation, because explorations can provide their own rewards. For me, few things bring more pleasure than making radical new hypotheses—and then showing that their predictions are correct, despite the objections of my competitors.

Artist: It seems almost the same to me, because nothing can surpass the thrill of conceiving a new kind of representation and then confirming that this will produce new effects in my audience.

Psychologist: It seems clear that many such achievers regard their ability to function in spite of pain, rejection, or adversity to be among their outstanding accomplishments!

In any case, all this suggests that ‘exploration pleasure’ (however it works) may be indispensable to those who want to keep extending their development.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-5. What controls the mind as a whole?

Jean Piaget: “If children fail to understand one another, it is because they think they understand one another. … The explainer believes from the start that the reproducer will grasp everything, will almost know beforehand all that should be known. ... These habits of thought account, in the first place, for the remarkable lack of precision in childish style.[23]

How do human minds develop? We know that our infants are already equipped at birth with ways to react to certain kinds of sounds and smells, to certain patterns of darkness and light, and to various tactile and haptic sensations. Then over the following months and years the child learns many more perceptual and motor skills, and proceeds through many stages of intellectual development. Eventually, each normal child learns to recognize, represent, and reflect upon some its own internal states, and also comes to self-reflect on some its intentions and feelings—and eventually learns to identify these with aspects of other persons that it observes. This section will speculate about possible structures we might use to support those activities; the next section will suggest some ideas about how children might develop these.

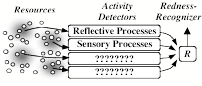

This book has proposed several different views of how a human mind might be organized. We began by portraying the mind (or brain) as based on a scheme that deals with various situations by activating certain sets of resources—so that each such selection will function as a somewhat different “way to think.”

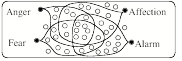

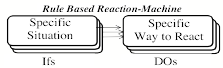

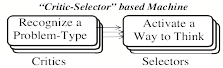

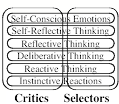

To determine which set of resources to select, such systems could begin with some simple sorts of "If–>Do" rules. Later these develop into more versatile "Critic–>Selector” systems.

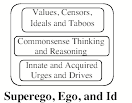

Chapter §5 conjectured that the adult mind comes to have multiple levels of organization. Each level has Critics to recognize situations and Selectors that can activate appropriate ways to think, by exploiting the resources at its own and at other levels . We also noted that these ideas could be seen as consistent with Sigmund Freud’s early view of the mind as a system for resolving (or for ignoring) conflicts between our instinctive and acquired ideas.

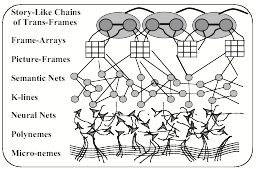

In chapter §8 we also reviewed various ways to represent knowledge and skills, and noted that these could be arranged in a stack with increasing degrees of expressiveness.

Each of those ways to envision a mind has different kinds of virtues and faults, so it would make little sense to ask which model is best. Instead, one needs to develop Critics that learn good ways to choose when and how to switch among them.

Is a Mind like a Human Community?

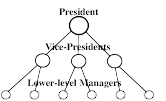

Perhaps a more popular model of mind portrays our mental processes as like a human community—such as a residential town or a company.[24] In a typical corporate organization, the human resources are (formally) organized in accord with some hierarchical plan.

We tend to invent such ‘management ‘trees’ whenever there’s more than one person can do; then the work is divided into parts, which then are assigned to subordinates. This picture suggests that one might try to identify a person’s Self with the Chief Executive of that company, who controls the rest through a chain of command in which instructions tend to branch down from the top.

However, this is not a good model for human brains because an employee of a company is a person who might be able to learn to perform virtually any new task—whereas, most parts of a brain are too specialized to do such things. [25] This difference may be important because, when a Company becomes wealthy enough, it may be able to expand itself: when it wants to include new activities, it can hire additional employee-minds. In contrast, we humans don’t (yet) have practical ways to expand our own individual brains. So, whenever you add a additional task (or break a large one into smaller parts)—and then try to do them all at once—then each sub-process will lose some of its competence, because it now has access to fewer resources. Perhaps we should state this as a general principle.

The Parallel Paradox: If you break a large job into several parts, and then try to work them all at once—then each process may lose some competence, from lacking access to resources it needs.

There is a popular belief that the brain gets much of its power and speed because it can do things many things in parallel. Indeed, it is clear that many of sensory, motor, and other systems do many things simultaneously. However, it also seems clear that as we tackle more complex and difficult goals, we increasingly need to divide those problems into subgoals—and then focus on these sequentially. This means that our higher, reflective levels of thought will tend to operate more serially.

This is less of a problem for a company, which can often divide a problem into parts, which it then can pass down to separate subordinates, who can deal with them all simultaneously. However, that leads to a different kind of cost:

The Pinnacle Paradox: As an organization grows more complex, its chief executive will understand it less, and will need to increasingly place more trust in decisions made by subordinates. (See §§Parallel Paradox.)

However, many human communities are less hierarchical than the companies that we just described, and make their decisions by using more cooperation, consensus, and compromise. [26] There is usually some ‘leadership,’ but in a working democracy, those leaders are somehow given authority by the membership to help, when needed, to assist in making decisions and settling arguments. Such negotiations can be more versatile than ‘majority rule,’ which gives to each participant a spurious sense of ‘making a difference’—whereas that feeling ignores the fact that almost all differences get cancelled out. This raises questions about the extent to which our human ‘sub-personalities’ cooperate to help us accomplish larger jobs—but we don’t know enough to say much about this.

Central and Peripheral Controls

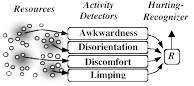

Every higher animal has evolved many resources that can interrupt its ‘higher level’ processes, in reaction to certain states of affairs. These conditions include such signs of possible dangers as rapid motions and loud sounds, unexpected touches, and the sighting of insects, spiders, and snakes. We also react to such bodily signs of aches and pains, feelings of illness, and such needs as hunger and thirst. Similarly, we are subject to more pleasant kinds of interruptions, such as the sights and smells of foods to eat, and of signals of sexual interest.

Many such reactions work without interrupting most mental activities—as when your hand scratches an insect bite, or when you move into shade to avoid excessive light. A few of these mainly instinctive alarms are: Itching, impending collision, hunger, thirst, bright light, excessive heat or cold, losing one’s balance, loud noise, pain, hearing a growl or snarl, seeing a spider, insect, or snake.

We are also subject to alarms that seem to come from ‘inside the mind’—such as when we detect an unexpected pattern or opportunity, or a failure of some process to work, or a conflict between our goals and ideals. Here are a few of these mainly acquired, internal alarms, many of which could be represented by using Critics, Censors, and Suppressors: phobias, obsessions, and sense of surprise; failure of a plan or goal; grief, guilt, shame, or disgust; and conflicts among one’s goals and ideals.

While most alarms could be handled by a Critic-Selector model of mind, one also could take a less centralized view, in which the processes that we call ‘thinking’ are affected by a host of other, partly autonomous processes. For example, one could think of a city or town as an entity whose processes are influenced by the activities of sub-departments concerned with transportation, water, power, fire, police, school, planning, housing, parks, and streets—as well as legal and social services, public works, and pest control, etc., each with its own sub-administrations. Can one think of a city as having a Self? Some observers might argue that each town has a certain ‘ambience’ or ‘atmosphere,’ and certain traits and characteristics. But few would insist that a city or town has a ‘sentient’ personality.

Reader: Perhaps that’s because they don’t have your idea that a “Self,” is a network of models, each of which may help a system to answer questions about itself. But in fact, each of those departments for planning, power, parks, and streets—and each of those other agencies—have plenty of diagrams, charts and maps that represent aspects of the town they’re in.

I cannot disagree with that—except to argue that, usually, few of those maps or models are accessible to the other departments. Perhaps if all those different representations were assembled into efficient panalogies, the resulting system might indeed seem to have more of a personality.

Programmer: I like some of your theories about how minds work—except that all of your schemes seem far too complex for a system that functions reliably enough. What happens if some of its parts break down? A single error in a large computer program can cause the entire system to stop.

I suspect our human ‘thinking processes’ frequently ‘crash’—perhaps as often as several times per second. However, when this happens you rarely notice that anything’s wrong, because your systems so quickly (and imperceptibly) switch you to think in different ways, while the systems that failed are repaired or replaced. Here are a few of the kinds of failures that are likely to get somewhat more ‘attention.’

You have trouble recalling past events.

You have trouble when solving an urgent problem.

You cannot decide which action to take.

You’ve lost track of what you were trying to do.

Something has happened that surprises you.

Nevertheless, in cases like these, usually you still can switch to other productive ways to think. For example, you might change the domain you are searching through, or select some other problem to solve, or switch to some different overall plan, or make a major switch in emotional state—without knowing or even being concerned with why your original project might have failed.

Furthermore, it seems possible that, whenever some of your systems fail, your brain may retain some earlier versions of it. Then in situations where you get confused, you may be able to ask yourself, “How did I deal with such things in the past?” Then this might cause some parts of your mind to ‘regress’ to an earlier version of yourself, from an age when such matters seemed simpler to you. This suggest another reason why we might like the idea of having a Self:

“One's present personality cannot share all the thoughts of all one's older personalities - and yet it has some sense that they exist. This is one reason why we feel that we possess an inner Self - a sort of ever-present person-friend, inside the mind, whom we can always ask for help.”—§17.01 of “The Society of Mind.

However, we should not ignore the tragic fact that people also are subject to failures from which recovery may be difficult, or impossible. For example, if something went wrong with the machinery that controls your Critic/Selector processes, then the rest of your mind may become reduced to a disorganized cloud of inactive resources, or get stuck with some single, unswitchable way to think.

"The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age."—H.P. Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu"

Mental Bugs and Parasites.

If a mind could make changes in how it works, it would face the risk of destroying itself. This could be one reason why our brains evolved so many, partly separate systems, instead of a more unified and centralized one: there may have been substantial advantages to imposing limits on the extent to which our minds could examine themselves!

For example, no single Way to Think should be allowed to have too much control over the systems we use for credit assignment—because then it could make itself grow beyond bound. Similarly, it would be dangerous for any resource to be able to keep enforcing its goals, because then it could make the rest of the mind spend all its time at serving it. The same would apply to any resource that could control our systems for pleasure and pain—for any resource that found a way to completely suppress some instinctive drive might be able to force its person to never sleep, or to work to death, or to starve itself.

While such drastic calamities are rare, a great many common disorders do result from the growth of such ‘mental parasites.’ For many human minds do indeed get enslaved by the self-reproducing sets of ideas that Richard Dawkins entitled “memes. ” Such a collection of concepts may include ways to grow and protect itself by displacing competing sets of ideas. [27] (I should note that many such sets of beliefs are so widespread that they are not regarded as pathological.)

However, many people are so clever that, when their minds get occupied by those ‘mental parasites,’ they may invent or find some social niche in which they can ‘make a living’ by recruiting yet other minds to adopt those same sets of strange ideas.

[Another class of bugs: thinking too much and getting in circles.] Nevertheless, the problem of meandering is certain to re-emerge once we learn how to make machines that examine themselves to formulate their own new problems. Questioning one's own "top-level" goals always reveals the paradox-oscillation of ultimate purpose. How could one decide that a goal is worthwhile -- unless one already knew what it is that is worthwhile? How could one decide when a question is properly answered -- unless one knows how to answer that question itself? Parents dread such problems and enjoin kids to not take them seriously. We learn to suppress those lines of thoughts, to "not even think about them" and to dismiss the most important of all as nonsensical, viz. the joke "Life is like a bridge." "In what way?" "How should I know?" Such questions lie beyond the shores of sense and in the end it is Evolution, not Reason, that decides who remains to ask them. (from “Jokes and the Logic of the Cognitive Unconscious.”

To protect themselves from such extremes, our brains evolved ways to balance between becoming too highly centralized, or too dispersed to have much use. We had to be able to concentrate, yet also respond to urgent alarms. We still needed some larger-scale organization because no much smaller part of us could know enough about the world to make good decisions in all situations

Why don’t we have more bugs than we do?

In the evolution of our brains, each seeming improvement must also have brought additional sorts of dangers and risks—because every time we extended our minds, we also exposed ourselves to making novel types of mistakes. Here are some bugs that everyone’s subject to:

Making

generalizations that are too broad.

Failing to deal with exceptions to rules.

Accumulating useless or incorrect information.

Believing things because our imprimers do.

Making superstitious credit assignments.

Confusing

real with make-believe things.

Becoming obsessed with unachievable goals,

We cannot hope to ever escape from all bugs because, as every engineer knows, most every change in a large complex system will introduce yet other mistakes that won’t show up till the system is moved a somewhat different environment. In any case, such failures are not uniquely human ones; my own dog also suffers from most of those bugs.

Each human brain is different because it is built by pairs of inherited genes (each chosen by chance from one of the parents). Also, many of its smaller details depend on other events that happened during its early development. So an engineer might wonder how such a machine could possibly work in spite of so many possible variations.

In fact, it was widely believed until recent years, that our brains must be based on some not-yet-understood principles, whereby every fragment of process or knowledge was (in some unknown manner) ‘distributed’ in some global way so that the system still could function in spite of the loss of any part of it. Today, however, we know that many functions do depend on highly localized parts of the brain. However, the arguments in this book suggests a different solution to this: we have so many different ways to accomplish most important jobs that we can tolerate the loss of some skills, because we may be able to switch to another.

In any case, each human brain has many different kinds of parts, and although we don’t yet know what all of them do, I suspect that many of them are involved with helping to suppress the effects of defects and bugs in other parts. Consequently, it will remain hard to guess why our brains evolved as they did, until we build more such systems ourselves—to learn which such bugs are most probable.

∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞

§9-6. Why makes feelings so hard to describe?

A color stands abroad

On solitary hills

That science cannot overtake

But human nature feels—Emily Dickinson, [28]

We usually don’t find it hard to compare two similar kinds of stimuli. For example, one can say that sunlight is brighter than candle light, or that Pink lies somewhere between Red and White, or that a touch on your upper lip is somewhere between your nose and your chin. However, this says nothing about those sensations themselves. Instead, it is more like talking about the distances between some nearby towns on a map—while saying nothing at all about those towns.

Similarly, when you try to describe the feelings that come with being in love, or from suffering fear, or when seeing a pasture or a sea, you’ll soon find that you are mentioning other things that these remind you of, instead of what those feelings are. And then, perhaps, you will come to suspect that one can never really describe what anything is; one can only describe what that thing is like—or what that that thing reminds you of.